Over the years I had enjoyed making ‘educational’ programmes as this was an excuse to meet interesting medics and learn ‘stuff’ which benefitted my patients.

One programme that sticks in the mind, though, was interviewing Bill Frankland’ the ‘father of allergy’. He had led a fascinating life – including surviving being a Japanese prisoner of war. Here he is talking to me about his life’s work. (You might have to click on ‘Browse YouTube’ to start the video)

There was little time for this sort of thing now as running a single-handed practice was very much a full time job. Clinical work was a joy (despite the long hours) as I had known many of the patients for decades and seen their kids grow up and have kids of their own. They knew we’d been given a hopelessly inadequate financial package and I knew the reason the practice had survived was because of their unflagging support – so there was an understanding that we were all in the same boat … all on the same side and fighting the same battles.

Sometimes when young Mums-to-be came along with their mothers for an antenatal check I used to get out the old Sonicad I had when I first started out in general practice to listen to the foetal heart. This was very different to the tiny gadgets we use today – it was the size of a shoebox. It amused me to be using the same instrument I’d used on the mother when the daughter, now expecting her first baby, was still in the womb … and the spirit of continuity seemed to appeal to them too.

The ‘spirit of the blitz’ involved branching out into areas not usually considered to be part and parcel of general practice. We were a source of free advice – so this proved useful to many. For example, if I saw somebody who was depressed because their line-manager was making their lives unbearable, giving antidepressants would merely be papering over the cracks. We’d need to sort out the underlying cause. Apart from giving advice on how to deal with the situation I’d often provide a ‘sick-note’ giving the reason for absence as “stress at work.” This put the employer on notice that there was a problem that needed to be dealt with.

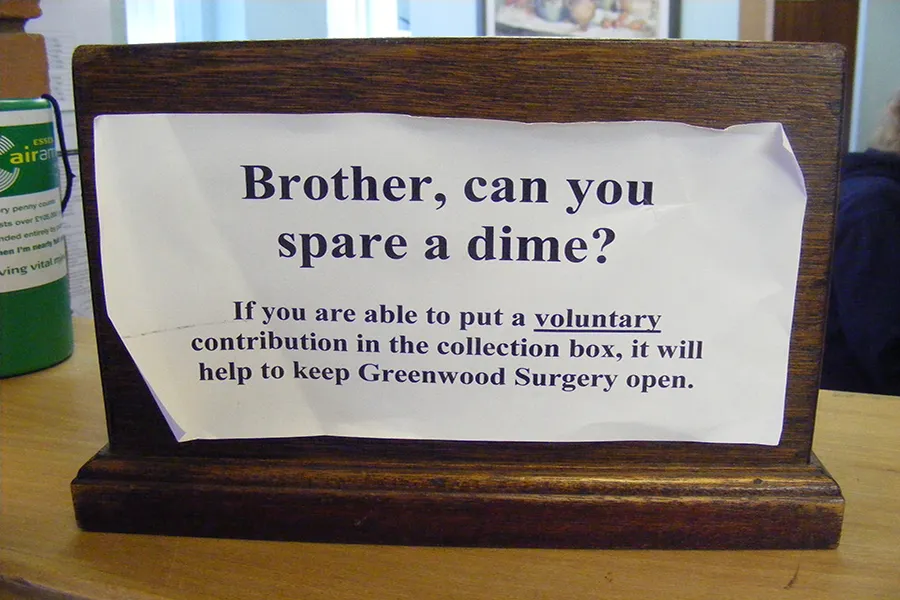

The funding for the practice had always been a problem. The NHS (which uses bizarre rules, such as the much derided Carr-Hill formula, for calculating funding) took the view that the residents of South Woodham were too rich, too young and too healthy to have the same needs as other areas. In leafy Danbury, though, where house prices were sky high, the situation was better. Now, however, we were in an altogether different situation: the practice had been set up to fail by the PCT. This caused knock-on effects – for example the cutting of seniority pay (which is given to GPs in recognition of long years of service to the NHS). From 2004 onwards, however, a large chunk of the seniority payment due to me was clawed back. Indeed sometimes I got nothing at all as, if a GP earned less that £26,970, 100% of it was clawed back – and, according to my accountant, I was her first GP client to have made a “pensionable loss.”

The reason given for this state of affairs was that a GP has to earn a certain amount to justify the seniority payment. The rationale, presumably, is that GPs who work just a handful of hours a week don’t really deserve it – but, although I was regularly working a 14 hr day and coming in at weekends, I was penalised because the budget I’d been given wasn’t enough to allow me to pay myself the minimum wage for the hours I put in. No account was taken of the fact that I was looking after far more patients than the average NHS GP. So this was a case of me being fined by the NHS for being underpaid … by the NHS. There was discretion to waive this rule but, needless to say, the PCT didn’t see fit to do so.

There was also a concerted effort to find ways of cutting the practices finances still further. For example, one PCT employee (who was well aware of our precarious financial situation) wrote to a district valuer with whom she was on first name terms to try to persuade him to reduce the rent reimbursement for the surgery building. (GPs at that time usually owned the surgery buildings and the NHS paid rent in order to cover the costs.) She wanted him to only reimburse us for part of the building … although it was entirely given over to NHS use. I repeatedly asked her if any other practice in the PCT area had received the same treatment and she repeatedly said she didn’t know – despite it being obvious that the PCT must have had this information. It took a very long time and many letters to resolve the situation – which was the last thing I needed on top of the hours I was spending dealing with clinical matters. I took the view that this sort of tactic was intended to push the practice into bankruptcy and thereby benefit the PCT run practice.

Dr John Cormack