I came to South Woodham from Cambridge where I was lucky enough to be one of the first students at the new Clinical School which was based at that time in ‘Old Addenbrooke’s’.

I had to pay my own way, as this was considered to be a “second first degree” – but this was no hardship as I had previously qualified as a dentist at The London Hospital, so I could work part time while I studied. This meant I was relatively well-off in comparison to most of the other medical students – so I could run my own sports car and immerse myself in the ‘buzz’ of the University town.

I did my hospital jobs at Addenbrooke’s (which by time had moved to the New Site). This included a stint with the late, great Prof Roy Calne, the pioneering transplant surgeon. This was exhausting – it was a ‘one in two’ meaning that, as well as working a full week, you were on-call every other night, and every other weekend. The weekend shift meant that you could work for almost four full days without a break – starting on Friday morning and ending on Monday evening – with very little sleep. On top of that, we could be involved (as spectators) with a liver transplants, which took place at night, because that’s when theatres were available for long periods. Prof. Calne had amazing stamina – I once watched him operate all night – and then, when I was asleep on my feet, he carried on with the routine morning list.

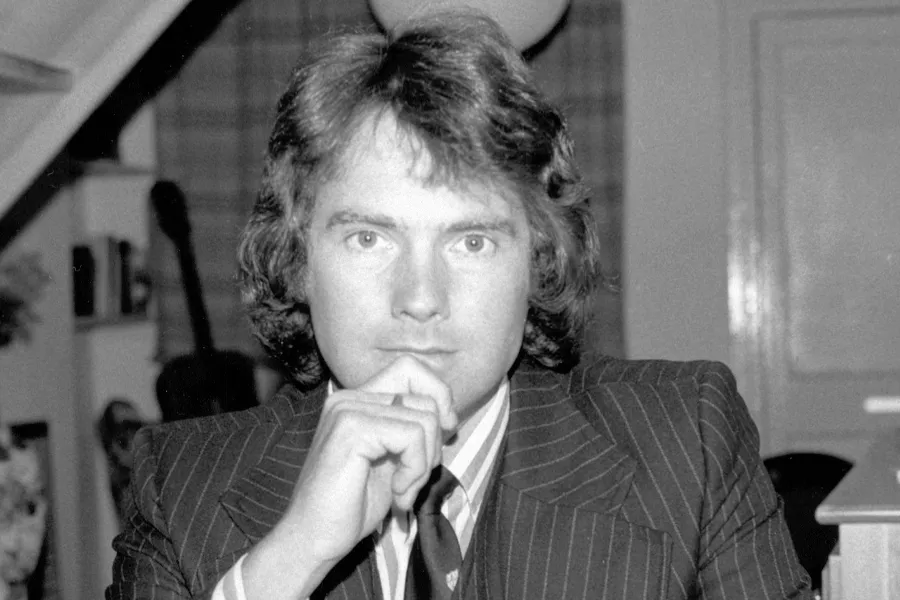

Whilst a medical student, I got involved with comedy shows, and eventually, having developed delusions of grandeur, took these to e.g. the Edinburgh Fringe, the Nottingham Playhouse, and on three occasions to the West End (for short runs). The latter came about because I got in touch with Brian Rix (who at that time was running the Cooney-Marsh theatres) and I offered to put on a season of shows called ‘Best of the Fringe’. I met him at his office and we shook hands on a deal in far less time than it recently took me to book a hall at the Willy D School.

I found life on the fringes of ‘showbiz’ exciting – but my sensible wife (Sue) thought it was the time that I grew up and got a proper job as we had a baby on the way – my daughter, Laura, who is now an NHS consultant. I spent a very happy six months in a lovely practice in Norfolk (while continuing to live in Cambridge), filling in for an absent GP – but then, as the 1970s drew to a close, decided to move a bit closer to friends and family, and a job in Essex came up.

This was the offer of a partnership at Dr Sylvia Ingold’s single-handed practice in Kingsway. I’m racking my brains to remember why I decided to accept the job – South Woodham Ferrers was a new town, which had been created by Essex County Council, with absolutely no thought for healthcare facilities. There had been mention of an intention to build a health centre – but nothing ever came of this.

Before the town had expanded rapidly, GP cover had been provided from Wickford and then, latterly, by the Danbury practice (using a caravan parked in what is now Warwick Parade.) By the time I arrived it was being provided from two houses built for residential purposes, – Dr Patel’s practice in Champions Way and Dr Ingold’s practice. Dr Ingold also provided an antenatal clinic in the old tin chapel in Hullbridge Road at one time.

Sylvia had her good points. For example, she had an obs and gynae qualification (MRCOG) so she did regular surgical lists at the local hospital (St Johns). A woman with a gynae problem could come in and see her at the practice on a Monday and be on her NHS operating list the next day – a pretty good service! She did have ‘eccentricities’ though. She was a chain-smoker so tears would flow freely from the eyes of anyone brave enough to enter her consulting room. She also had a loud voice – so, given that the wall that separated her consulting room from the waiting room was paper-thin, there wasn’t much privacy. One poor chap came in one evening with a problem in the ‘behindular region’, and she asked him to remove his trousers, which was reluctant to do as he’d just come home from work and hadn’t had time to shower. He asked if he could come back for the examination – but she insisted that he should remove his trousers. By this time, the people in the waiting room, who were keen to get home for their suppers, were losing patience – so they also entreated him to “get ’em off”.

This was before the days of disposable (paper) couch rolls so she had a cotton sheet on her examination couch, which was never changed while I was working there. It reminded me of the shroud of Turin in that there was an imprint of all the bodies that had lain on it.

Similarly, there was no privacy at all in the old tin chapel. One patient (Kate … who later joined my practice as a member of staff) told me of an incident that occurred when she was very young and easily embarrassed. When she saw Dr Ingold in the chapel (out of sight of those waiting in the pews, but not out of ear-shot) she became flummoxed when asked the date of her last period. (It was more important to be sure of this then than it is now that other means of checking are readily available) As she walked back down the isle she faced the disapproving gaze of the other Mums to be when Dr I’s parting remark rang out: “You may be responsible for the death of your unborn child”.

Being ‘on-call’ in those days were interesting. At that time GPs were on call 24 hours a day, seven days a week – although, in practices with more than one GP, there were rotas. There were no mobile phones in those days, so you had to be in contact with a landline at all times (which made life very difficult ) GPs were called out to everything – heart attacks, strokes, surgical emergencies, accidents – you name it. Nights and weekends weren’t quite as bad as they were in some practices as patients weren’t sure if they get through to me or her. If it was her, I was told her first words were: “Well, you better be dying!“

The strange and amusing stories that circulated about her make her sound worse than she was in real life. To take this in context, she was what was described as “a character“ and the world was a very different place back then. She did have a following and she looked after her patients pretty well.

And I don’t want anyone to go away with the impression that I was a superior being. I lacked experience (a much undervalued commodity in today’s NHS) and I was rather full of myself. Indeed my head was so far up my own fundamental orifice that I could inspect my own tonsils. I managed to get away with it because I was ‘the young doctor’ so people made allowances. And it wasn’t overly long before it dawned on me that I wasn’t quite so special after all.

Tune in for next week’s exciting episode.